One of the aspects of video games that was momentarily touched on before being (mostly) crushed by the flood of next-gen shooters with advanced graphics was the idea that games can connect with a person and affect them emotionally. You had complex characters who did more than simply move forward firing guns at everything that didn't look like them (either because it's a strange creature or simply someone who doesn't live in the same country as you) and you had stories that dealt with real issues. Later, "morality systems" were introduced in games, but they generally had as much real effect on the story as if you simply gave your character a blue shirt instead of a red shirt. Other games that dealt with disasters tended to eventually simply fall into matters of using guns on other people. In Disaster Report, there are guns, but they're always being held by other people, and you simply have to do your best to get around them.

Some games, however, decided to do more, and one such was Kazuma Kojo's Zettai Zetsumei Toshi series. Renamed Disaster Report in the United States, the first game dealt with the aftermath of a powerful earthquake striking what is essentially a man-made island. Your character, Keith Helm, has to try to get across the island to where people are being rescued while attempting to avoid aftershocks and floods and helping (or ignoring) other people attempting to survive like you are.

One thing that grabbed me regarding the game was the fact that the disaster wasn't simply set dressing. In many games, if you introduce some disaster, it's usually just to set the stage for some other kind of conflict. As much as the Dead Rising games originally talked about the importance of surviving a zombie apocalypse, it wound up being that the zombies were just things to make it harder to get from Point A to Point B in order to fight other human enemies.

In Disaster Report, you need to keep track of every item you pick up, whether it's a canteen, a wire coat hanger, or a car jack. You need to keep yourself hydrated, and you need to watch the character's stamina. If you push him too hard, he won't be able to make an important jump or climb across that wire. However, if you take too many breaks, you risk the aftershocks that occasionally strike the island catching you where something bad will happen.

Oh, and there's limited storage space, so good luck with that.

The game also spent a great deal of time making you deal with difficult choices. You meet one girl whose little brother has gone missing and is in a different direction from the path you're taking to get to rescuers. You can either make the journey with her to save her brother, or you can simply stay on your path and go "good luck, you're on your own!" There are moments where aftershocks rock a building you're in, and you have to choose if you're going to try to rescue someone else in the building who's injured (and thus require you to use more health and thirst resources later) or leave them behind and hold on to what you've scavenged together. If you wind up with a companion through the game, you suddenly find yourself splitting your supplies with another person, making each action you take even more important as you track your thirst levels and health.

The game makes the aftershocks an extremely big deal. One of the key control buttons is the "brace" button, allowing you to crouch down and grab the ground. This can keep you from being tossed around and injured, but it might also leave you prone when a floor collapses underneath you, a skyscraper topples onto you, or you simply aren't able to get out of the way of falling debris. You can also attempt to get to safety, but again, you might simply be running somewhere that winds up being more dangerous than if you stayed still.

Normally, this kind of "well, you might or might not die depending on the whims of the game" business would drive me insane, but I like it here, because it makes a lot of sense. You don't know what the best choice would be in a disaster, and to simply have one button solve the problem every time wouldn't be faithful to the struggle to survive.

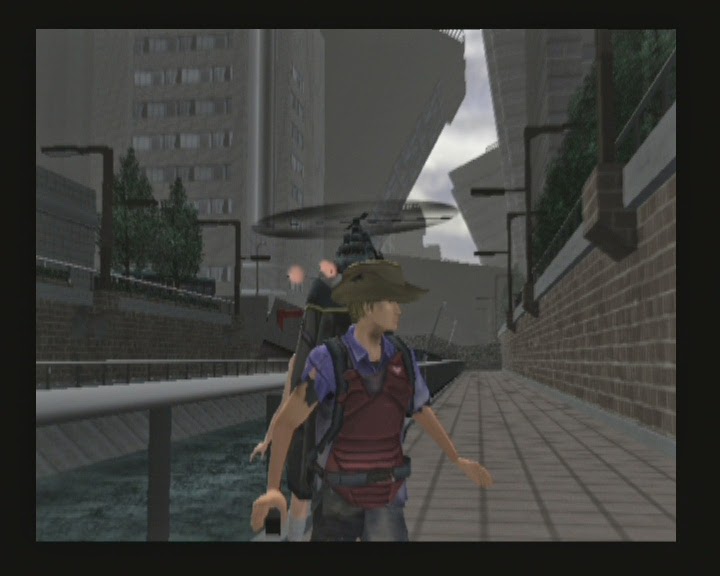

|

| However, it is generally advised that if skyscrapers are starting to topple over behind you, running forward is a good idea. |

Character interaction is also used in the game, as you can build relationships with the characters you meet. If a character starts to tell you their story, you can either calmly listen or disregard it. Someone asks you for help or tries to get you to go a certain direction, listening or ignoring them will change how they feel about you. This won't always affect game play in a major way, but with a few key characters, how they feel about you will be key in determining what kind of ending you get.

Oh, that's right, there's also multiple endings. The game pays attention to your actions and uses those to shape a reasonable end to your story. If you do things one way, you might wind up being rescued alone, while other options have other survivors with you. There's also a chance the game ends with your character simply bracing himself for the inevitable as the island slowly sinks beneath the waves, or perhaps you have another character there to hold your hand as you face your fate together. In one telling of the game, I managed to get to the helicopter just to realize the girl I had spent the entire game surviving with (Kelly) hadn't made it. She was stuck and needed help. The pilot was insisting that there was no time left to go and get her. I had to decide whether I went back and helped this person I bonded with through the game or if I simply shrugged and put her life behind me.

Now, I know "atmosphere" gets tossed around a lot, but in this game the sense of being alone really does come to haunt you. I found myself walking through empty streets and buildings privately wishing I'd stumble upon a group of rag-tag survivors, just so I'd get more of a sense of hope from the game. One of the buttons is the "call out" button, and I frequently found myself approaching ledges and platforms and calling out to emptiness, hoping to find someone else. I did my best to maintain good relationships with other characters, figuring not only does it help to know there's other people struggling with me, but that they might come in useful in later situations that require more than one person.

A lot of research was done by the game designers of what happens during disasters. They went back and looked at a lot of older films and manga for influences, but did their best to try to not let the game be too "Hollywood." Again, your character engages in almost no violence in the game. The only real thing you do towards the end is try to disrupt a helicopter with a fire hose, but there isn't even a "punch/shoot/attack" button in the game.

|

| "Okay, here's the plan. We sit here and whimper and hope he doesn't see us." |

If I had to pick a game that I really, really wish more game companies would attempt to recapture the magic of it would probably be this one. I would even be happy if someone could get the studio to release the fourth title in the series, which was completed just before the earthquake/tsunami struck Japan. The company has essentially scrapped the game following that. The company has also pretty much done everything they can to erase the fact they even existed, taking down all websites devoted to their games, pulling them from gaming networks like the Playstation Network, and essentially pretending the franchise (or any other game they made) never happened.

To me, when people ask "can video games be art," this is the game I want to point them towards, not Shadow of the Colossus or Journey or any other game. Letting the player even remotely experience the tension of surviving after something completely beyond our comprehension happens (and something that isn't even really malevolent, we're simply irrelevant to it happening) is an amazing experience.

I also just learned recently that there was a sequel released in the United States called Raw Danger! I am already attempting to find a copy. It will be mine.

No comments:

Post a Comment